When the citizenry perceives Singapore’s citizenship to be too easily obtained, it is difficult to drum up support for immigration by the government on its own citizens.

“What Does It Mean to Be Singaporean?”

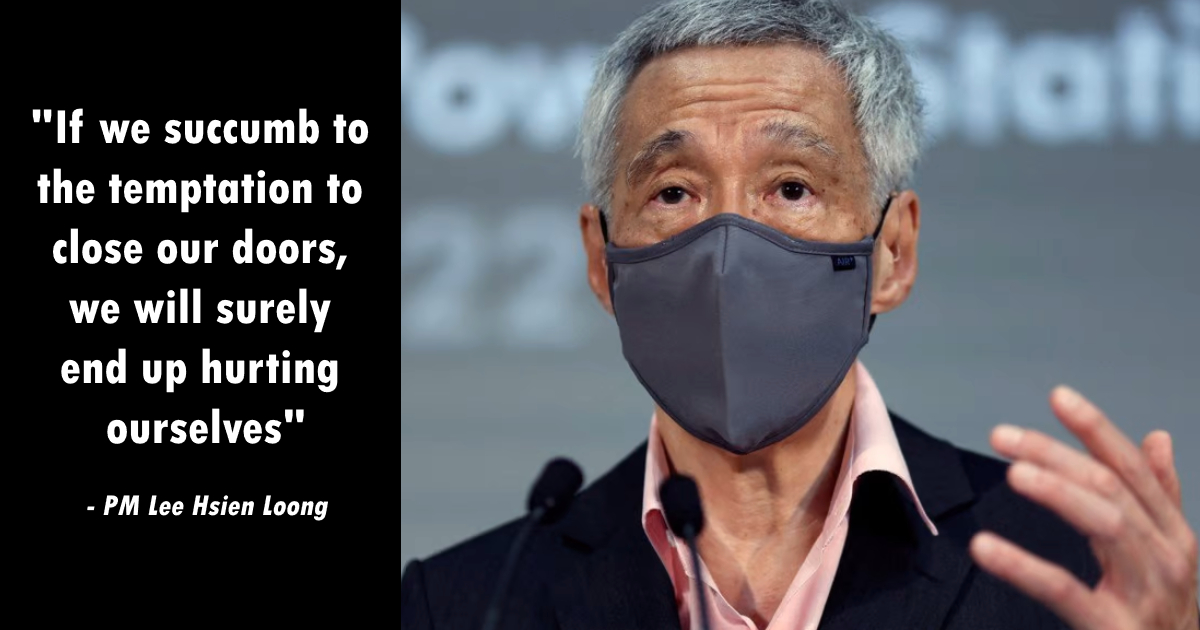

At the opening of Dyson’s New Global Headquarters at St James Power Station on 25 March, PM Lee emphasised the need for Singapore to remain open to foreign talents. Time and again, the government reminds its citizens that Singaporeans must welcome foreigners to give them jobs and sustain the economy. But if Singaporean society were to be defined by its readiness to embrace foreigners and its heavy reliance on them, what is left of the Singaporean soul? Do we have a strong national identity? What does it mean to be Singaporean?

“The ethos of our society must remain open – welcoming of new ideas and talent, always learning from others, never becoming resistant to change or complacent about the need to stay ahead. This is how we have built Singapore – drawing in the best scientists, designers, and engineers from around the world, embracing the diversity of ideas and cultures that congregate here, adding our own Singapore touch to make it work in our context.”

PM Lee Hsien Loong at the opening of Dyson’s new headquarters

The question of “what does it mean to be Singaporean” has been one that existed since Singapore became independent in 1965. A major impetus for the political differences between Singapore and Malaysia was the debate over whether the then-Federation of Malaysia (with Singapore as a member state) would be a “Malay Malaysia” or a “Malaysian Malaysia”, basing a common identity either on racial or nationalistic lines.

The societal angst in Singapore over the Singaporean identity, and correspondingly the value of a Singaporean citizenship has only grown over the past two decades. This was largely fuelled by an increasingly globalised economy and evolutions in human labour movement patterns that transcended traditional boundaries of borders and citizenship.

National Identity

The Singaporean government has sought throughout the country’s independent history to couch the national identity of “being a Singaporean Citizen” through the lenses of common morals and values. As the Singaporean national pledge stated so succinctly,

“We, the citizens of Singapore, pledge ourselves as one united people, regardless of race, language or religion, to build a democratic society, based on justice and equality, so as to achieve happiness, prosperity, and progress for our nation”.

But there is no denying that on the ground amongst Singapore’s citizenry, lofty morals and ideals used to define citizenship in our country often play second fiddle to far more bread-and-butter, not to mention more tangible and emotionally charged criterions used to judge if someone is a “true blue Singaporean”.

Has someone served National Service in Singapore? What has someone contributed in taxes or professional accomplishments in the name of being a Singapore citizen? How many generations has someone’s family been in Singapore? How long has someone been a pink-IC carrying citizen of Singapore? Does someone have family and children here? Can they speak English well? Where do they stay in Singapore? Where do they work in Singapore?

All these are just a myriad of more pragmatic and immediate displays of “citizenship” to the average Singaporean on the streets, in judging and critiquing whether someone they’re interacting with, or sharing common space with, is truly a “Singaporean”. This is however something that is little understood nor empathised with by Singapore’s government ministers and national leaders.

Citizenship Criteria

Singapore lacks a firm and codified route towards citizenship as some countries do elsewhere in the world. For example, in countries like the UK, Australia, Canada, the US, and even the Netherlands, new citizenship applicants are required to take citizenship tests that are administered in the format of multiple-choice questions. The tests are done as a way to discern and determine both the language proficiency of the applicant in the native language of the respective countries, as well as whether they know enough about the societal customs, norms, and values of the country they’re applying for citizenship. The implied meaning behind such tests is: if you bother to learn enough to pass such tests, you’re committed enough to stay for the long-haul.

The lack of citizenship tests as one of several potential concrete barriers to entry in Singapore’s immigration doctrine and process is a major contributor to the perception divide between what the government sees as a pragmatic necessity of keeping Singapore globally competitive and welcoming to global talent, and the citizenry’s view on the ground that new citizens come and go as they please into Singapore, with little to no long-term commitment towards Singapore, nor understanding and permanent integration into local society.

When the citizenry perceives Singapore’s citizenship to be too easily obtained, too easily changed, and with an opaqueness as to how someone is determined as suitable to become a citizen, it is difficult to drum up support for immigration by the government on its own citizens who would naturally feel aggrieved that they are “competing with foreigners with no stake in their lands or affairs”. This is the root sentiment behind online anti-government slogans like “NS for Singaporeans, jobs for foreigners”, as well as increasing anecdotal questioning by individuals in society of others being “Singaporean enough”, based on how recently they or their parents immigrated into Singapore.

Xenophobia or Lost Identity?

Singaporeans by and large are not xenophobic. Many of us have forefathers who were immigrants themselves. Our country is rightly described to be one built up by the efforts of migrants, as well as transient foreign workers in our various critical industries.

But the difference between the migrants who built up Singapore since 1965 or even earlier under British colonial rule and migrants today is the fluidity of how money and people can flow across borders. In the past, people migrated and money followed to stay in a new country for good.

Today, citizenship is one often seen to be easily valued and changed in monetary and geopolitical terms. A Singaporean passport would be seen more favourably than other regional Asian passports, both to travel as well as apply for third-country citizenships for many Western countries. Like it or not, a Singaporean citizenship is now a valuable mercenary tool to be used by globalised, footloose, and financially-able individuals seeking the best interests for themselves.

As it currently stands, a growing proportion of Singapore’s population no longer know what it means to be Singaporean anymore. When Singaporean society and Singaporeans no longer have a concrete grounded idealism of what “being a Singaporean is”, it is almost inevitable to subsequently see the bubbling up of anti-foreigner sentiments, misconceptions of external immigrants adding further competition and congestion to our society and employment markets, and sometimes naked xenophobia as a coping mechanism for locals seeking to vent their frustrations about other areas of their lives in Singapore.

A Critical Issue to Address

“What does it mean to be Singaporean” becomes a much more critical question to ask in a globalised world where nation-state borders are increasingly porous and there is greater need to reconcile differences between the government and its citizenry. The ongoing Covid-19 pandemic might have reduced the ease of relocation for prospective new citizens, but it won’t be a state of matter that will exist forever.

If Singapore is to have a strong, united core in facing the challenges of the 21st century, then the issue of the Singaporean identity, and the government’s gatekeeping of what it means to be a Singaporean citizen will need to be urgently addressed in a pragmatic, down-to-earth, and realistic manner by both the government and the people it rules.

Measures like citizenship tests might help in alleviating concerned perceptions on the ground about new citizens getting citizenship too easily. But they are merely a short-term panacea in the ultimate questioning of what a uniquely Singaporean national and personal citizenship identity should look like in a globalised future. Defining a national identity and what it means to be the citizen of a country can be done through morals and ideals, but it still has to translate into tangible and visible gate markers that effectively differentiate and elevate citizenship beyond short-term mercenary meaning.

The alternative would be national ruin, brought about by the implosion of Singapore’s society due to distrust by its citizenry against its government, seen not to put enough effort in defending and valuing Singaporean citizenship in immediate, tangible terms.

who asked him to close the door? he meant, like north korea?

he’s supposed to do what other countries have been doing all the while …

PROTECTING THE JOB MARKET