It was announced on June 1 2022 that Malaysia-based YTL Power International has completed its acquisition of fallen Singaporean corporate darling Hyflux’s Tuaspring power station.

The concluded deal was worth $331.45 million in total, of which $270 million of the deal was paid outright in cash by the Malaysian power producer, itself a subsidiary of YTL Corporation, a major Malaysian infrastructure conglomerate.

YTL Power International also owns Geneco, one of seven electricity retailers in Singapore open electricity market.

“You will own nothing… and you will be happy.”

This is the latest in a long history of major Singaporean strategic industry companies being sold off into foreign ownership.

Neptune Orient Lines (NOL) was sold off to French shipping company CMACGM in 2016 for $2.5 billion. Singapore Petroleum Company (SPC) was sold off to Chinese state-owned energy company PetroChina in 2009 for $1.47 billion.

In the same year, Singapore’s Chartered Semiconductor Manufacturing (CSM), the world’s third largest dedicated independent semiconductor foundry was sold to an Abu Dhabi technology investment company for $2.5 billion and integrated with its own joint venture chip manufacturer (GlobalFoundries) in cooperation with American company Advanced Micro Devices (AMD).

Even Singapore’s National Iron and Steel Mills (NatSteel) underwent Indian ownership between 2004 and 2021 when TataSteel, India’s largest steel manufacturer bought the company business and name for $486.4 million before selling it back to Singaporean metals trader Toptip Holding in 2021 for $172 million.

How Can Foreigners Succeed where Singapore Failed?

Recent world events in the past few years have driven home the importance of national control and ownership of strategic industries such as shipping logistics, energy, and microchip production.

Yet in all such industries where Singapore used to have major multinationals with major state stakeholdings, they have mostly been divested and sold off for short-term immediate profits to individual and corporate shareholders such as Temasek Holdings.

Reasons for their selling-offs were largely attributed to inherent issues with the companies’ corporate cultures, or the unviability of certain industries in Singapore after cost-based analysis.

However, such companies suddenly achieve profitability and purpose once in foreign ownership, which begs the question of what went wrong with our local corporate leadership figures, especially if they came from the political establishment or had heavy state support to begin with.

Case Study 1: Neptune Orient Lines (NOL)

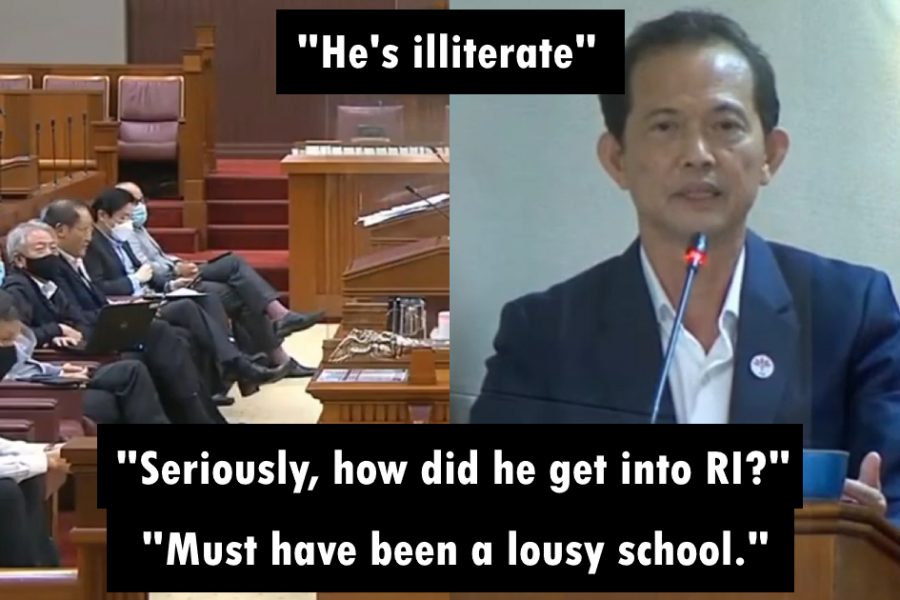

A good example of this would be NOL’s sale to CMAGCM. NOL’s CEO at the time of its sale to CMACGM was retired Chief of Defence Force Lieutenant-General Ng Yat Chung; he had been appointed NOL CEO in 2011 and helmed the company for five years till the 2016 sale.

For five years he failed to turn around the fortunes of the company or adapt it to changing times, instead conveniently choosing to blame structural issues within the company for it lacking the “scale and agility” to compete in the modern global shipping market.

Within a year of NOL’s sale to CMACGM, the company turned a profit of $26 million under the French shipping company’s management, delivering a stinging rebuke through practical results to Ng’s excuses of company structural issues with NOL that he couldn’t fix in five times the duration CMACGM used to make a profit on their newly-acquired business.

Case Study 2: Hyflux

Hyflux was once a corporate darling of Singapore and a key private industry player in securing Singapore’s strategic water supply interest, even appearing at the National Day Parade as a marching contingent in 2013.

Tuaspring was proposed in 2010 by the Public Utilities Board (PUB) to become Singapore’s second-largest water desalination plant, yet it was Hyflux’s corporate management’s greed of maximizing profits at the cost of prudent risk and debt management that drove them to build Tuaspring as a cogeneration plant for both water desalination as well as electricity power generation, despite never having any experience in the electricity open market and entering during a time of depressed electricity prices in Singapore.

This same greed also drove Hyflux to then take out a $720 million 18-year term loan facility to fund the development of the desalination and power plants from Maybank Singapore and Maybank Kim Eng Securities.

Quite how a company running one of Singapore’s strategic assets in the form of a water desalination plant was allowed to seek out bank loans from a Malaysian bank has never been explained, considering how up till 2013 Hyflux’s sole lead manager and bookrunner for retail and corporate investors was the Development Bank of Singapore (DBS).

Ultimately, Hyflux’s botched attempt at making Tuaspring a cogen plant for supplying both water and electricity made the entire plant a massive financial loss, and this resulted in Maybank calling in its loans to the company and finally its termination of collaboration with Hyflux.

Hyflux’s debts to its Malaysian creditor was the final straw that broke the camel’s back, and once again it was a Malaysian company (YTL Power International) that benefited from the whole fiasco by purchasing Tuaspring out of Singaporean ownership.

Case Study 3: Chartered Semiconductor Manufacturing

Recent news carried talk of Taiwan’s Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC)’s potential interest in setting up a new multibillion dollar factory in Singapore to diversify and expand its production lines to cope with the ongoing global microchip shortage.

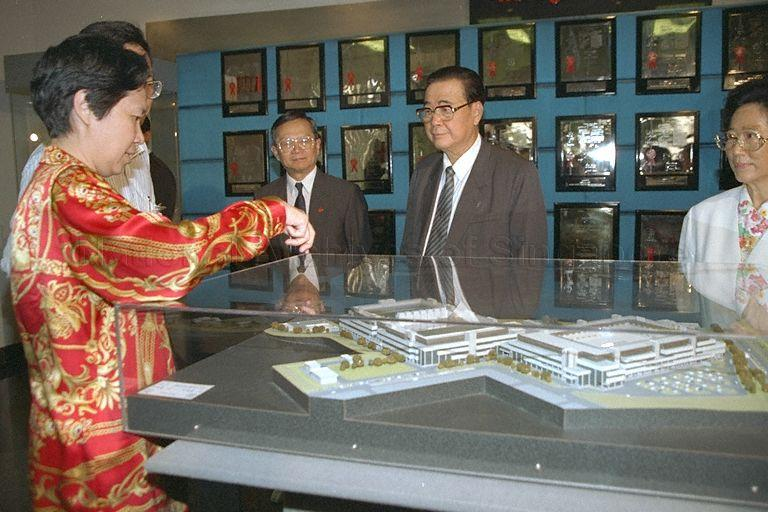

Yet Singapore once had its own chip manufacturer to be proud of and hold a stake in such a globally important strategic market: Chartered Semiconductor Manufacturing (CSM). CSM used to be wholly state-owned thanks to its outright purchase by ST Engineering in 2000, and later under Temasek Holdings after 2004.

Yet again a combination of short-term corporate greed in maximising profits from Temasek without stomach in long-term investments into this strategic asset, as well as lack of technical and scientific competence within CSM itself thanks to an overreliance on outsourcing work to external contractors led to the company’s failure to compete in the global microchip manufacturing market.

CSM would ultimately be sold in in 2009, under the direct chairman leadership of Ho Ching (former CEO of Temasek Holdings, and the wife of current prime minister Lee Hsien Loong).

One must wonder now with the benefit of hindsight how Singapore would have benefited from retaining CSM as a major chip foundry given the current global microchip shortage and seen profits from long-term investment into the domestic skilled manufacturing and engineering field.

National Profiteering From Asset-Stripping

Former British prime minister Harold Macmillan once famously warned about how “…the sale of assets is common with individuals and the state when they run into financial difficulties. First the Georgian silver goes, and then all the nice furniture that used to be in the saloon. Then the Canalettos go. I venture to question the using of these huge sums as if they were income… Modern economists have decided there is no difference between capital and income. I am not so sure.”

His criticism of Thatcherism in the 1980s and the rampant asset-stripping the UK saw of its public services and strategic industries by the ruling Conservative government of the day sounds eerily applicable to Singapore’s brand of government management and stewardship of the country’s strategic assets and industries.

Singapore’s political leadership has demonstrated little understanding of the difference and importance in safeguarding our country’s capital, be it human or industrial, in favour of quick-profiting income achieved through flipping and selling strategic businesses and undercutting the local workforce with cheaper imported foreign labour on employment passes.

Has Singaporean society felt the benefits of such monetary profits and savings? Or are we poorer and less secure as a society for all of it?