On 11 August 2022, a Burmese covert activist group by the name of Justice For Myanmar (JFM) released an online article in which Singapore was named front and centre as a major facilitator for arms supplies to the Burmese military junta.

According to the article, some 116 Myanmar and Singapore companies with 262 directors and shareholders were documented to have brokered the supply of weapons and other equipment to the military junta in contracts worth millions of dollars since 2017, with some 38 subsidiary or associated companies being based in Singapore.

Myanmar’s Military Dictators Strike Back

Myanmar has had a difficult history with brutal military dictatorships and tenuous democratic governance. The Burmese Armed Forces (Tatmadaw) first seized power in 1962 through a coup overthrowing the country’s first democratically elected government that they had previously voluntarily restored barely two years earlier in 1960. The 1962 coup marked the beginning of the military junta dictatorship under various generals, with various attempts by them to whitewash their political legitimacy through rigged constitutional processes and sometimes outright denial of free election results. Myanmar is currently under a renewed and brutal military dictatorship led by General Min Aung Hlaing, ever since the Tatmadaw once again overthrew the democratically elected government of Aung San Suu Ki in a coup on 1 February 2021. Since then, there has been what amounts to an all-out civil war being waged in various parts of the country between the Tatmadaw and the National Unity Government (formed in exile by remnants of the previous democratic government alongside various regional ethnic militias).

Singapore’s Role in Facilitating Myanmar’s Arms Deals

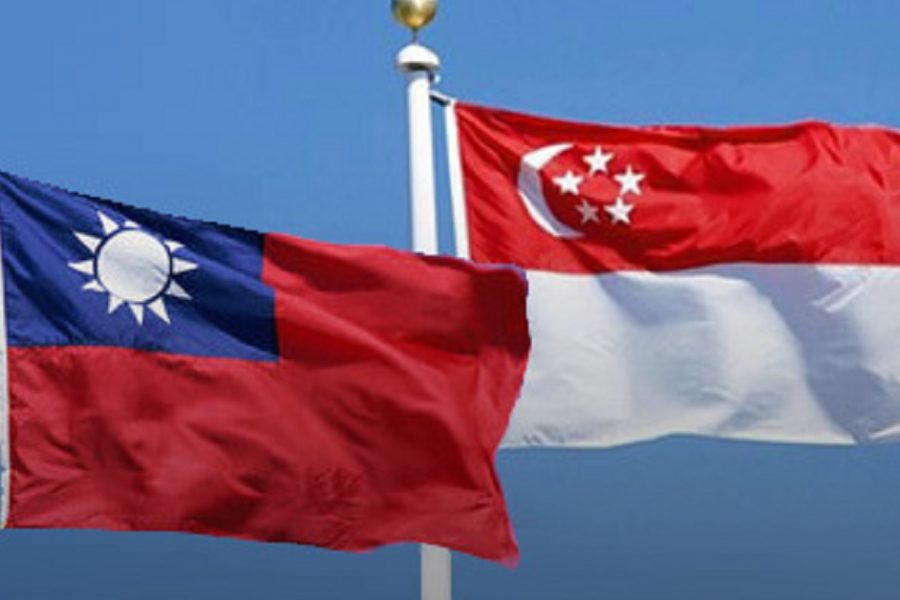

According to JFM’s online article, Singapore’s important role in propping up the Burmese military junta through facilitation of US financial sanctions evasion and arms sales conducted by subsidiary and associated companies in the country is laid bare both in terms of sheer numbers, as well as the significance of some individuals and deals that have been ongoing since before the 2017 Rohingya genocide and after the 2021 coup.

For example, the Belarus Honorary Consul to Myanmar, Dr Aung Moe Myint has a business unit registered in Singapore under the name “Dynasty Excellency Pte Ltd” as part of his Dynasty Group. Dr Aung is openly named as one of several state-sanctioned arms dealers by the Tatmadaw junta back in January 2022, and it is highly suspected that this Singapore-based company is involved in facilitating arms trade transactions between Belarus and Myanmar, specifically in importing parts from Belarus for Russian-made Mi-17 military helicopters used by the Tatmadaw in their military operations.

Another example would be Dr Naing Htut Aung, who is also another officially sanctioned Tatmadaw arms broker. Dr Naing previously ran a Singapore-registered company by the name of “Venture Sky International Ltd” between 2016 and 2021; the company was responsible for at least 12 contracts with the Myanmar Air Force to supply spare parts for its MIG-29 fighter jets, various transport aircraft, and Mi-17 military helicopters. According to JFM, these contracts were worth between USD44 thousand up to an eye-watering USD3.3 million.

The above are but two examples of Singapore-based but Burmese-owned companies with ties to the military junta actively circumventing existing international sanctions and providing important logistical support for the Myanmar Air Force. This is significant as the Myanmar Air Force had been heavily involved in the Rohingya Genocide since 2017, as well as the ongoing civil war in Myanmar through indiscriminate bombing campaigns against ethnic rebels in the country. Various other companies incorporated in Singapore but owned by individuals linked to the military junta also helped facilitate various other arms trade deals for equipment such as radar sets, naval equipment, and other dual-use goods and funds to the Tatmadaw to sustain its oppressive and illegitimate rule over Myanmar in the face of international condemnation and sanctions.

Myanmar Funds and Arms Deals: Singapore’s Dirty Little Open Secret?

It’s not like Singapore’s government knows nothing about such dealings. In April 2022, the US Department of State Counselor Derek Chollet penned an op-ed that was published in Singapore’s English state media newspaper The Straits Times. This op-ed was published the same day that Chollet announced in a speech given to a US-based thinktank that some 65 individuals and 26 businesses have been sanctioned by the US for their close ties to the Tatmadaw military junta, and described the commitment by the US to use targeted sanctions and active measures limiting arms access to the Tatmadaw junta as the means to ratchet up pressure against the regime to cease its illegitimate rule of Myanmar and indiscriminate violence inflicted to enforce said rule.

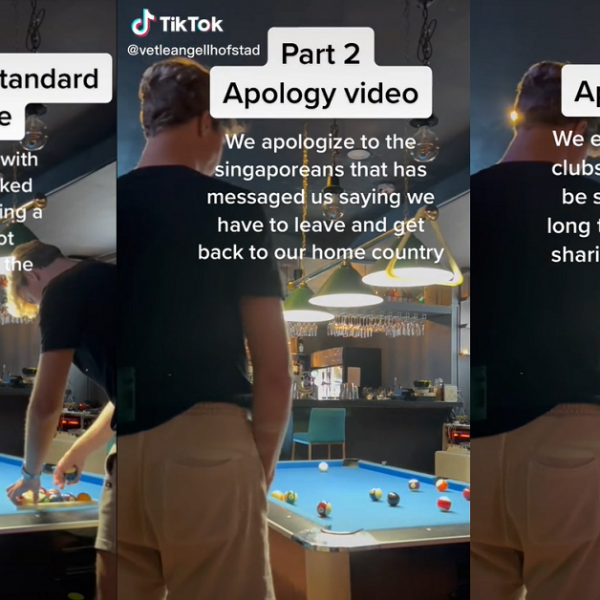

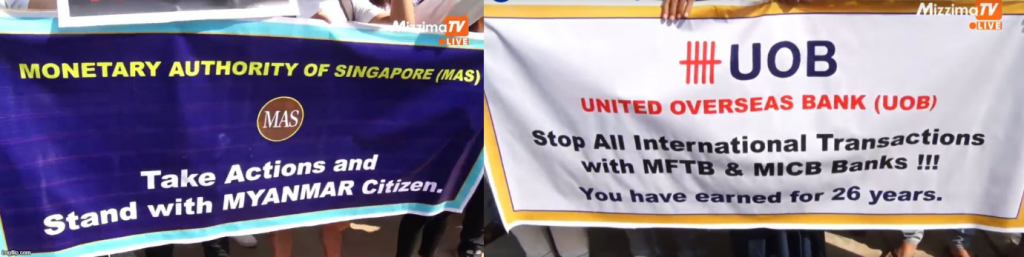

Singapore’s financial leverage and enabler status for much of the Myanmar junta’s international trade and access to global finance had been previously highlighted by the US and various global activist organisations as an important focal point for applying pressure against the military junta in Myanmar. Yet Singapore continues to hide behind the opacity of its banking institutions enshrined in Section 47 of its Banking Act, alongside its non-signature of the Arms Trade Treaty or the Wassenaar Arrangement (two important international treaties prohibiting arms and dual-use goods from being knowingly transferred to governments engaged in genocide, crimes against humanity or war crimes), to turn a blind eye on junta-linked funds and business dealings conducted through its economic system. Justice For Myanmar’s regular exposés of arms deals and sanction-evading trade conducted through Singapore, as well as repeated lobbying by various Western powers such as the US for Singapore’s help in enforcing international sanctions on Myanmar make a mockery of the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS)’s assertion in February 2021 that it had “not found significant funds from Myanmar companies and individuals in banks in Singapore”.

Singapore’s Diplomacy with Myanmar: “Thoughts And Prayers”.

On the diplomatic front, Singapore has not deviated much from its usual tactics of mealy words of little strength and much passivity. Despite concerns that Myanmar’s latest military coup and renewed dictatorship rule poses a threat to Singapore’s business interests in the country (Singapore is the top foreign investment source in Myanmar since 2014), as well as the overall credibility of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) which Singapore is one of the strongest members, the only escalations in rhetoric and taking a stand against the Tatmadaw junta’s brutal imposition of dictatorial rule on Myanmar from Singaporean leaders only went as far as reheated hand-wringing labelling from 2007 such as “not acceptable”, “disastrous”, “a national shame” and “an unfolding tragedy”.

Further diplomatic pressure in the form of ASEAN’s excluding of Myanmar’s junta leaders from any ASEAN meetings to deny them legitimacy is supported by Singapore, but that is as far as things go as ASEAN and Singapore continue to fall back slavishly on their historical non-interference stance dating back from the Non-Aligned Movement of the Cold War.

In August 2022, Singaporean Foreign Minister Vivian Balakrishnan gave the most pithy summation of the diplomatic learned helplessness that ASEAN and more importantly Singapore has displayed in the face of escalating military violence in Myanmar: “We can’t interfere, but if they do not see that there is value in dialogue, national reconciliation and making use of Asean’s good offices, then I’m afraid it’s a very dire situation”.

“The Only Thing Needed for Evil To Flourish… is for Good Men to do Nothing.”

Nobody is asking for military intervention in Myanmar by Singapore or any ASEAN country; not only does it go against the ideological stance of non-interference that holds the regional bloc together, few countries in ASEAN are capable of such armed intervention against Myanmar’s well-armed military in the first place.

However, whilst active armed intervention is out of reach and diplomacy is rapidly running out of time against an intransigent regime that Lee Kuan Yew once described as “dense and stupid… (like) talking to dead people”, shutting off the Tatmadaw junta’s access to Singapore for facilitating trade with Singapore-incorporated companies and circumventing financial sanctions through Singapore’s financial system is easily done with the plethora of open evidence available for global scrutiny.

Singapore’s excuse of not imposing or supporting the imposition of broad sanctions against Myanmar for fear of “hurting its poverty-rife population” is a cheap cop-out when in reality even Myanmar’s civil society resisting the military junta’s brutal and violent dictatorship is calling for these very sanctions. After all, many of such sanctions requested are targeted explicitly at cutting off military funding and logistical support to the Tatmadaw junta, not at wholesale economic sanctions on civilian goods and services needed by Myanmar’s civil society. Singapore’s inaction even on such targeted military and financial sanctions means that the blood of Myanmar’s civil society shed by the military junta in the ongoing civil war also stains its hands.

Old Habits Die Hard

In 1994, Singapore then-Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong became the most senior ASEAN leader to visit Myanmar under its military junta on an official state visit. This came in the wake of serious political violence and a bloody coup by the Tatmadaw junta in 1988, and was widely seen in retrospect as emblematic of Singapore and ASEAN’s diplomatic missteps in gifting political and international legitimacy to a military regime which was never going to engage in good faith with any diplomatic effort to have it change its violent ways and restore civilian rule.

It seems that Singapore’s dirty little Myanmar secret has long and deep roots in history, and the well documented and continuous exposés of Singapore’s ongoing facilitation of military arms sales and utilisation of its financial system by organisations such as Justice For Myanmar stand in sharp contrast to the diplomatic duplicity and learned helplessness practiced by Singapore over Myanmar’s junta dictatorship.