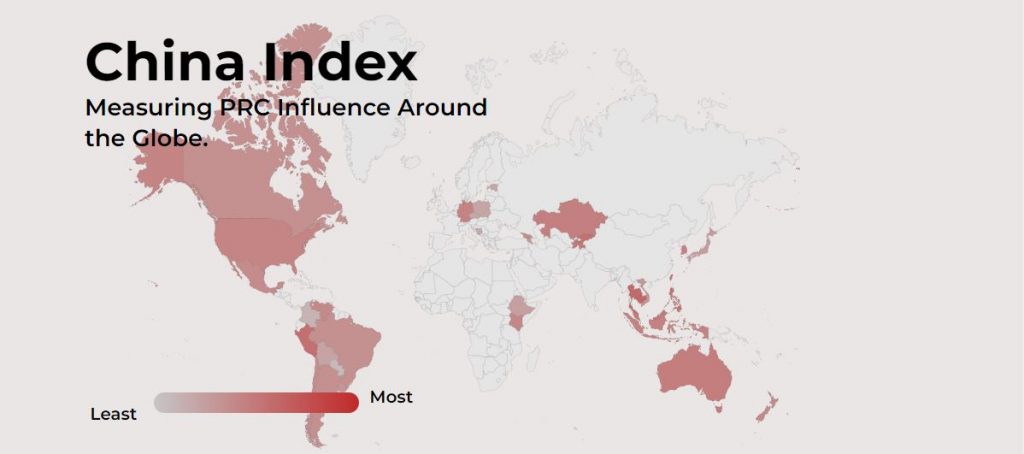

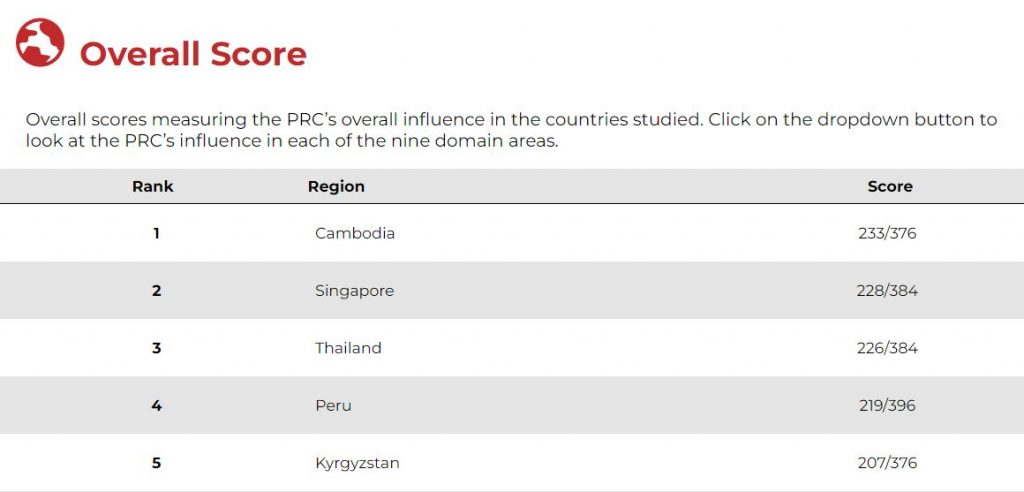

Singapore’s international news presence in the past week has largely been dominated by its ranking as the second-most influenced by China in a new “China Index” report produced by a relatively-new Taiwanese thinktank, DoubleThink Lab. In its report, Singapore was listed as being especially susceptible to Mainland China’s exposure, pressure and effect of Beijing’s influence in certain domains such as technology, society and academia, and was second only to Cambodia in terms of PRC influence.

Quite how Singapore has landed in such a state internationally, to be labelled as “especially susceptible” to PRC influence operations and geostrategic pressure is a stark example of how much the tables have turned over the past decades for Sino-Singaporean relations, with China’s global rise since the 1990s mirroring Singapore’s stagnation as an advanced society with an increasingly aimless sense of national identity.

“Power resides where people believe it resides, and even a small country can cast a very large shadow.”

It would be a mistake to see Chinese Influence in Singaporean society as simply as a historical and cultural inevitability; of a country with 5000 years of history and culture having uncontestable clout and influence over another with an émigré colonial background and independent for only 57 years.

Even during Singapore’s early decades, the country stood tall as one of the few pro-Western bastions in South East Asia that stood up to Chinese-funded and incited Communist political and militant movements that plagued much of the region during the 1960/70s Cold War decades. This was especially remarkable considering how Singapore is the only independent state in South East Asia that had a Han-Chinese racial majority, yet managed to stay clear of Communist Mainland China’s attempts at exporting Chinese-style Communist revolution to its shores.

It was from this position of established anti-Sino-Communism credentials that Singapore played a pivotal role in China’s opening up to the world. This was something particularly facilitated through the personal diplomacy and advocacy of the country’s first Prime Minister, Lee Kuan Yew playing a bridging role between successive Chinese and US national leaders.

It was of strong significance that even before reaching the US Presidency in 1969, Richard Nixon had already consulted Lee in 1967 on the desirability of the US engaging with China, something which eventually happened in 1971 when Nixon met Mao Zedong on the first US presidential visit to Communist China.

From this fateful visit sprung China’s opening up to the international community and Western economies in particular, something which was further advanced in the 1980s under Deng Xiaoping’s leadership of the PRC which also drew significant influence for its own free-market reforms and governance models from Singapore.

It would be no exaggeration to state that modern-day China, with its status as the “world factory” of the international globalised economy would not have happened or existed in its current form without Singapore’s influence and assistance.

Turning of The Tables in an Age of Identity Politics

The reversal of roles between Singapore and China, from teacher-student to subordinate-superior in recent decades can be boiled down to a single word: Identity.

Specifically, this change in relationship dynamics between Singapore and China neatly corresponds with the rise of Chinese historical and cultural revanchism in its desires of redemption for its national identity, and the decline of Singaporean national identity in its pursuit of ever-deeper international business ties and enmeshing into the globalised international political community as a “Switzerland of the East”.

Both China and Singapore got rich off the rising tide of globalisation and Western-dominated international business and finance, but whilst China saw its newfound riches and rising global stature as fertile grounds for it to finally claim hegemonic power status in Asia and a redemption arc for its historical “hundred years of humiliation” in the 20th century, Singapore increasingly geared its society towards the pragmatic pursuit of financial prosperity and economic growth at all costs, even if it meant increasingly forgetting what its national identity stood for in driving the city-state’s desires for independence back in 1965.

“United we Stand…”

China has always had a history of pursuing international propaganda campaigns and influence operations in furthering its own national strategic ends. Codified as the “United Front” political strategy within the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), this strategy entails a complex and opaque set of local and international organisations designed to advance the CCP’s influence in industry and civil society.

However, Chinese international influence operations under the “United Front” strategy have intensified markedly in the past decade with Xi Jinping as China’s paramount leader, fuelled by his brand of increasingly virulent and aggressive Han-Chinese ethnonationalism that recognises no borders nor historical societal evolutions of Han-Chinese diasporas globally.

Motivated by China’s newfound status as a rich global power, a powerful narrative has been spun of how the Han-racial majority China’s rise is reflective of the Chinese Communist Party’s superior leadership and governance, and how all Han-Chinese raced people in the world should join together and bask in the glow of China’s success, and ideally even work towards it with their innate allegiances to the Motherland by virtue of blood and racial ties.

Cynicism and Whataboutism make for good bedfellows

Faced with such a narrative, Singapore with its increasingly weakened sense of national identity and societal pride has become “increasingly susceptible to Chinese influence”, as aptly described by DoubleThink Lab’s China Index Report.

When local news coverage broke the China Index Report and Singapore’s ranking within it, domestic reactions to it were disturbingly lacking in objective thinking or self-reflection.

Some Singaporeans interviewed for their reactions immediately stated their discrediting of the report along lines of bias (simply because it was published by a thinktank in Taiwan, which holds historical grievances against China and the CCP).

“For me, anything from Taiwan will be skewed towards Western views and interpretation… the findings will not be objective,” says retiree Ronald Lim, 76.

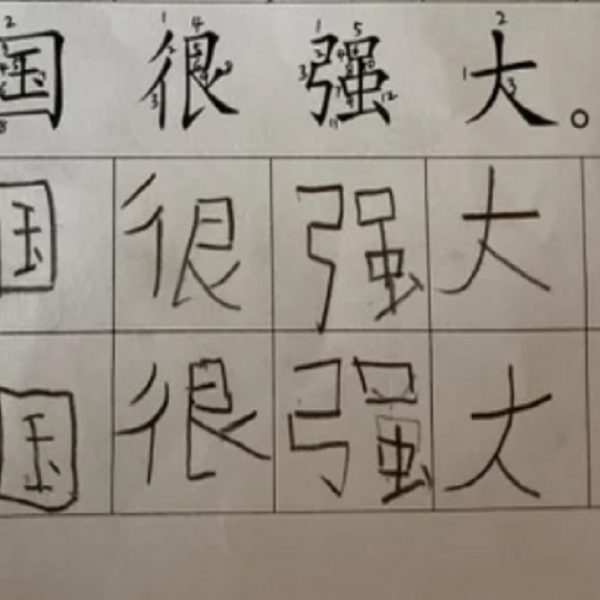

Some Singaporeans also stated that their acceptance or even welcoming of Chinese influence in Singapore was because they identify more with their “Chineseness” than the “Singaporean identity”, and they perceive a comparative lack of protection and advocacy for such a national identity by the Singaporean government.

As IT engineer Victor Low, 50, tells me: “My race is Chinese… I still feel part of the Chinese bloodline, and I want to see that bloodline prosper again, as it did hundreds of years ago.”

Mr Kilmar Wong, 43, who is self-employed, says he identifies more closely with Chinese traditions and values.

Mr Low says: “It’s not so much that I want to move to China or be a Chinese citizen, but I just feel that they are taking care of their people more so than the Singaporean government is taking care of Singaporeans.” He sees Singapore as the only place in the world where foreigners are more valued than locals.

Equally disturbing is how it seems that the Singaporean government has misjudged its priorities between safeguarding and propagandising racial harmony in multicultural Singapore with a 75% Han-Chinese ethnic majority, and deepening the roots of Singapore’s national identity in its effort to supplant racial identities with a single unified nationalist one.

Nobody will deny that Singapore is one of the best societies in the world when it comes to multiracial and multicultural coexistence in harmony. Yet in its zeal to pursue economic prosperity and growth at all costs, the Singaporean government has taken a very overtly internationalist and pro-foreigner line not just in its image to international business, but within its society to be as welcoming to foreigners and their influences they bring along, with no serious institutional vetting or initiatives to ensure true long-term integration for new immigrants.

“What is a Singaporean Worth to the Government?”

Singaporean society had been constantly bombarded with the narrative of “we are an island nation with no natural resources, we live and die on the largesse of international money and connections, so we can’t afford to be unwelcoming to them and must roll out the red carpet at all costs”.

Couple this with the underwhelming window-dressing efforts the government puts into maintaining ties with the Singaporean international diaspora or even encouraging them to return home with their foreign experiences to better local society, fuelled by a toxic institutional mentality most exemplified by former Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong’s “quitters and stayers” statement made in a 2002 speech, and you are left with a society where its citizens feel that they are ruled by leaders that put foreign interests ahead of domestic ones, where citizens abroad feel unwanted and abandoned, and with multiracial/cultural harmony advanced in local society only for its value in providing a peaceful and racial violence-free society for transient foreigners coming through the city-state.

“We all want to belong to something great.”

It is no coincidence that China’s economic rise is but a larger version of Singapore’s, since their political and economic engagement with the international community was largely facilitated and modelled after us. Both countries got rich, but one remembered what it was getting rich for, whilst the other forgot who it was getting rich for.

The progressive weakening of a Singaporean national identity, independent from racial or religious identities, makes it incredibly vulnerable to seductive foreign narratives of national superiority and influence that makes no distinction between ethnoracial, national, and political identities.

It is in this light that Singapore’s fall under Chinese influence should be viewed. Urgent questions need to be asked about what can be done to strengthen the national identity roots of Singapore with revamped civics/social studies education for society as a whole, and a reestablishment of the societal compact between local society and a government that can be rightfully said to be “of the people, by the people, for the people”.

Comments are closed.