Dr Mahathir’s comments come straight out of the playbook of whipping up nationalistic fervour by appealing to historical legacies and political rule by local societies in Southeast Asia prior to Western colonialism in the region.

Revanchism in Southeast Asia: A Clear and Present Danger to Singapore

In a rally speech titled “I am Malay: Survival Begins” to a gathering of Malay nongovernmental organisations called the “Congress for Malay Survival” on June 19 2022, former Malaysian prime minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad made inflammatory comments calling for Singapore and Indonesia’s Riau Islands to be returned to Johor State and the Malaysian Federation.

He justified this call by claiming historical justification and legacy given Singapore Island’s ownership and rule by the Johor Sultanate before British colonial annexation, as well as the historical ethno-existence of a Malay-dominant “Malay Land (Tanah Melayu)” stretching from Southern Thailand to the Indonesian Riau Islands.

How Western Colonialism Supplanted Regional Politics in the Past

National and regional politics in Southeast Asia are heavily shaped and influenced by historical ethnic and cultural legacies, as well as the effects of colonialism up to the present day.

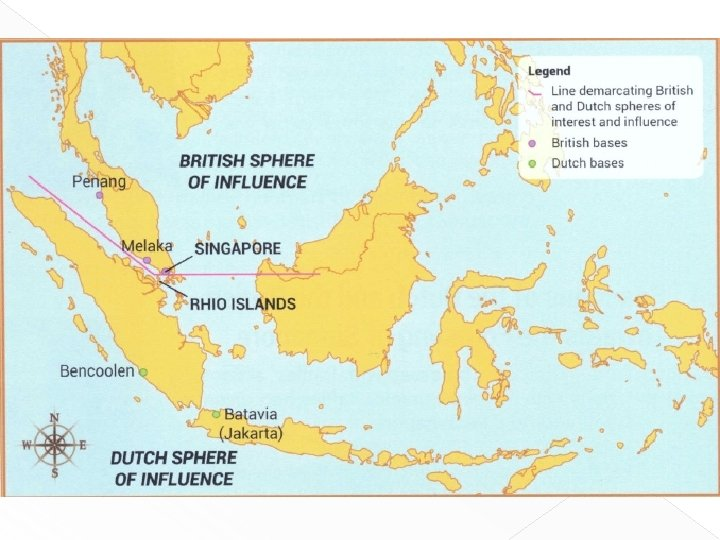

During the early 1800s, the territories of modern Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia were at the centre of a major power struggle between the British and Dutch for colonial spheres of influence in Southeast Asia.

This was majorly driven by continental European conflict during the same time period with the Napoleonic Wars, as the British had seized the Spice Islands and the entire island of Java in the Dutch East Indies in 1810 and 1811 respectively after Napoleon’s ultimate annexation of the Netherlands into the First French Empire in 1810.

The Malay World Splits In Two

The Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824 was the final effort by the British and Dutch to resolve the issue of colonial spheres of influence over Malayan and Indonesian territories under both powers, and one of its largest impacts was the forced partitioning of the Old Johor Sultanate which had control over much of Southern Malaya and parts of Southeastern Sumatra (including the Riau Islands). This was done entirely without any input by the Johor Sultanate nobility, and ended up creating two different puppet sultans ruling over the Malayan and Indonesian parts of the split sultanate.

The British retained control and influence over the Malayan part of the Johor Sultanate and returned conquered East Indies territories to the Dutch, whilst the Dutch retained its sphere of influence over the Indonesian part of the Johor Sultanate and renounce all territorial claims on Malaya.

The ultimate border between the British and Dutch spheres of influence would be set along the Straits of Singapore between Singapore Island and the Riau Islands; this would become the modern-day Singapore-Indonesia maritime border.

The Toxic Legacy of Western Colonialism on Regional Revanchism

This is the historical basis on which Tun Dr Mahathir’s comments were based on. It comes straight out of the playbook of whipping up nationalistic fervour by appealing to historical legacies and political rule by local societies in Southeast Asia prior to Western colonialism in the region.

The official term for such a phenomenon is called “revanchism”, whereby a political manifestation (be it organic or deliberately astroturfed) is propagated for the purposes of reversing and restoring territorial losses incurred by any country after armed conflicts or socio-demographic movements.

(Image: Then-Umno Youth chief Hishammuddin Hussein’s infamous keris-wielding speech in 2005 during the era of Umno’s ‘Malay Agenda’)

Given the ethno-centric nature of such historical political rule and societies along racial demographic lines, it is unavoidable that such revanchism often makes for good bedfellows with ethnonationalism espousing racial superiority and rule for the “majority race” in a country or region.

In this case, Tun Dr Mahathir is directly feeding into Malay conservative concerns in modern Malaysia of their rights and privileges as majority “bumiputera” being eroded under modern progressive political concepts of egalitarian rule without racial or religious favouritism, by stating that he “wonders if the Malay Peninsula will belong to someone else in future” if Malays are either weak and lose possession of their lands to external powers (as demonstrated by the Old Johor Sultanate’s partitioning) or poor and sell off their lands to non-Malay minorities and outsiders.

Justifying The Present By Using The Past I: The Philippines

Revanchism and its toxic effects on regional geopolitics and stability in Southeast Asia is not something that is just practiced by Malaysia. For example, under the rule of Ferdinand Marcos in the second half of the 1960s the Philippines had attempted to reclaim the eastern parts of Malaysia’s Sabah State on Borneo Island using revanchist justifications of Eastern Sabah being ruled by the Muslim Sultanate of Sulu between 1658 and 1700, and then subsequent Spanish colonial rule over the sultanate as part of the Greater Philippines. This was despite the Spanish ceding all control and claims over Northern Borneo including lands previously controlled by the Sulu Sultanate (which would make up Eastern Sabah in the Malaysian Federation) to the British under the Madrid Protocol of 1885.

Marcos had secretly set up and trained a military unit made up of Muslim Moro fighters to “destablise and take Sabah” under a mission provocatively named “Operation Merdeka”. When the Muslim Moro fighters found out their mission’s true objectives, most demanded to go home as they refused to kill fellow Malaysian Muslims in Sabah. This earned them heavy reprisal from Marcos in the Jabidah Massacre on 18 March 1968, where all but one individual from a particular batch of Moro fighters were killed by predominantly Christian army troops from the Philippines Armed Forces.

The Jabidah Massacre proved to be a major flashpoint for the Muslim Moro Insurgency in the Philippines, something that persists to the current day with various Muslim terrorist groups including the Islamic State of Lanao (a regional offshoot of the Middle East Islamic State terrorist group that famously besieged Marawi City in 2017). Even in February 2013, a descendant of the Sulu Sultanate sent some 200 Muslim militants in an unsanctioned “invasion” of Eastern Sabah to assert his self-declared historical claims to his sultanate’s territorial lands; this was ultimately put down by Malaysian armed forces within a month.

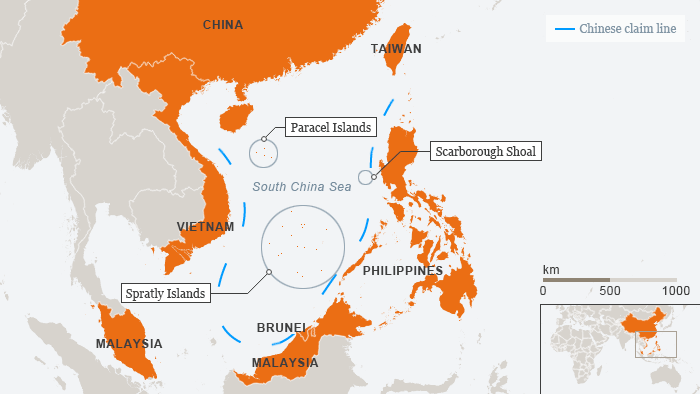

Justifying The Present By Utilising The Past II: China

Revanchism is also practiced by the largest power in Asia: China. Its claims to the South China Sea with its unilateral “nine dash line” territorial demarcations are heavily steeped in China’s callback to its imperial legacy under the Ming Dynasty, when Chinese imperial treasure voyages to Southeast Asia had garnered it significant tribute and trade from regional kingdoms such as the Sultanates of Malacca and Brunei, as well as strengthening its suzerainty over Vietnam.

By claiming historical heritage over both the naming of the South China Sea after China as well as so-called sovereignty over previously uninhabited islands in the maritime region, China is attempting to put forth a revanchist argument for ultimate territorial control over a major maritime region with one of the busiest trade routes in the world for its own geopolitical ends as well as perceived national pride as the predominant power in Asia.

The Impact Of Historical Revanchism on Singapore

Singapore’s status as the only Chinese-majority state in the Malay race-dominant Malayan-Indonesian archipelago region of Southeast Asia is perceived by many Malay politicians in Malaysia and Indonesia as an artificial creation by the city-state’s colonial legacy under British rule, where Chinese labour migrants escaping from Qing China’s political and economic disasters were actively encouraged to settle on Singapore Island as part of what they saw as British efforts to subvert local Malay and Muslim demographic and political influence in the region.

It is very clear from Tun Dr Mahathir’s reported comments at the recent Malay NGO meeting that such ethnonationalist revanchist sentiments still remain and persist as political tools, never mind the irresponsibility and irrationality such rhetoric espouse.

Such enduring revanchism poses a clear and present danger to Singapore, the result being that Singapore can never take its independence and national survival for granted. This is the fundamental reason underpinning Singapore’s heavy investment into military defence and its active diplomatic tie-building on the international stage for international support against any threat to its sovereignty.

The ongoing revanchist invasion by Russia against Ukraine is a sobering reminder of the toxic power that such historical revisionism can play in geopolitics, and the importance of maintaining Singapore’s armed forces as one of the strongest militaries in the region.

It is often said that “when there’s a will, there’s a way”, and Singapore can never take for granted that its neighbours will never one day find a way to act upon any revanchist will to reestablish their idea of a Malay-dominated geographic and political bloc in Southeast Asia.

Who is the author ?

Who is the author?